By Denise May Levenick

When emptying my deceased aunt’s home to prepare it for sale, we

didn’t have the time to go through all the contents of her closets and

drawers. A brief look showed that over the years, important documents

and photos had been layered with household receipts, brochures, junk

mail, bill stubs and random bits of paper.

I transferred individual drawers to boxes and brought everything home

to examine more closely. The first box I sorted showed me that this had

been a wise decision. Mixed in with free notepads from the local

realtor, I found two cabinet card photographs of my grandmother when she

was an infant and toddler. These treasures could have been lost

forever.

Lots of family archives are handed down in the same condition as my

aunt’s: a mess of heirlooms, historical documents and, well, trash. When

you’re the one in charge of dealing with the archive, it can be an

overwhelming responsibility. You’ve just inherited a lifetime worth of

stuff from a loved one (whom you may have recently lost). Now what do

you do?

In my book How to Archive Family Keepsakes, I explain how

you can organize, preserve and pass on what is meaningful and

important—without letting inherited items take over your house and your

life. Follow these steps to organize, manage and pass on your family

archive.

1. Keep only what’s important

Receipts. Newspaper clippings. Old letters. Scrapbooks. Address

books. All have one thing in common—they’re made from paper, in its many

colors, shapes and sizes. If your inherited archive is free from paper

trash, consider yourself lucky. I’ve worked with dozens of family

collections and more than half contained moderate to extreme amounts of

this type of trash. Why? Because paper is free or cheap, it comes to

you, it has many worthwhile uses and, for many people, it’s hard to

resist picking up that vacation pamphlet or restaurant take-out menu.

But all that paper can be too much. Saving vital information is one

thing, but saving an entire lifetime of cancelled checks is quite

another. As family curators, we might have just a teeny-bit of hoarding

tendencies in our own DNA. We find value in anything our ancestors might

have touched.

Be strong. You don’t want to end up on reality television with your

closets and cabinets thrown open to the world. When it comes to paper,

you can feel just fine about throwing away quite a bit—even if it came

from Great-aunt Helen’s desk drawer. As you begin to sort and organize

your archive, ask yourself: Is this item worth the time and the cost of

archival storage supplies to be part of my archive?

I suggest you evaluate the materials and categorize them as:

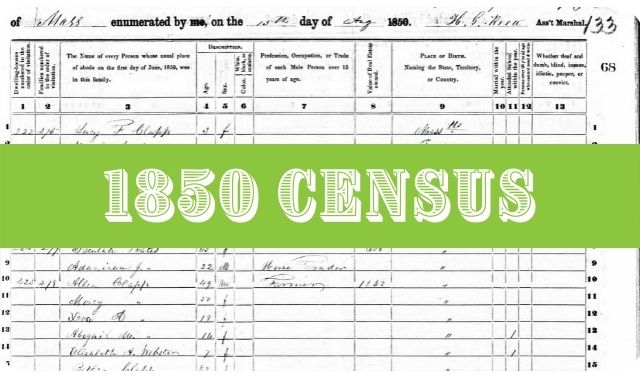

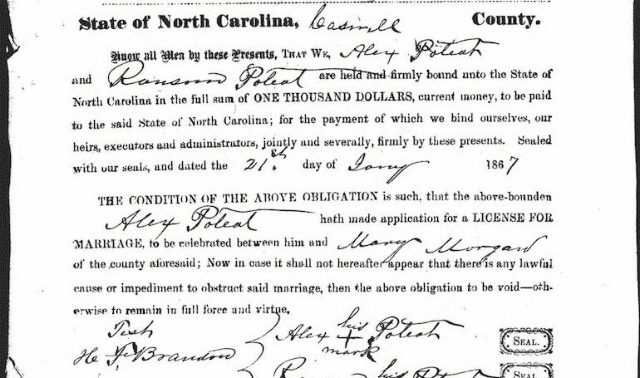

Vital

The paper gives genealogical information or other key information

about a person, place or event in your family; or it confirms or refutes

family tradition. Photos, letters, vital records, military discharge

papers and the like fit this description.

Be prepared to find photos and film anywhere and everywhere. I’ve

found old photos inside books, tucked in letters, curled inside a vase,

tacked to the back of a picture frame and underneath dresser drawer

paper lining. Wallet-size photos might be in wallets or purses. Tiny

photos were often trimmed for jewelry. Cased photographs such as

daguerreotypes might be mixed in with books or other artifacts. Look

everywhere and bring the photos you find to one place where you can

evaluate their conditions and arrange them for storage. Handle these

items with care and conservation.

Adds color

This paper adds color and interesting information about a person,

place or event in your family. You might classify a bulletin from your

ancestors’ church or brochure about their favorite vacation spot in this

category.

Store these items either with the “vital” items, or move

them to their own archival box. Digitize them as needed, and see to

their archival storage needs only after the vital items are taken care

of. If the information on a paper is more useful than the actual piece

of paper, consider saving the digital copy and discarding the paper.

Not archival

If a paper—such as a receipt, bill stub or unintelligible

notes—doesn’t add personal information, don’t bother saving it in your

family archive. Just because a loved one kept it, doesn’t mean you have

to. In particular, isolate anything made of newsprint or cheap-grade,

acidic paper. It’s not worth damaging your grandfather’s last will and

testament by stacking it with a crumbling cleaning receipt.

If the information is of interest to only you, or you might need it

for insurance or other purposes, keep it somewhere outside of the

archive. For example, I have a small plastic shoebox filled with 1950s

valentines, sweet bookmarks and other bits of ephemera that I use in

handmade collage and greeting cards.

2. Preserve and protect

Review all the items in your archive box by box and consider giving

your full attention and resources to only those items that really count.

Take care of the vital stuff first. When you are tempted to save odd

bits of cool ephemera, remember your original goal to preserve your

family history.

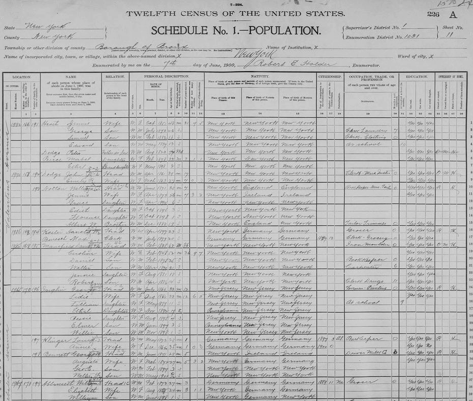

Paper

You have several options for organizing the papers you decided to

keep. You could sort them by the family member they’re associated with,

by surname, by size or by type (such as vital records, military papers

or school memorabilia). Depending on the size of your collection, you

might be able to fit all your papers for one person or surname in a

single folder, or you might need several folders.

As you work, carefully remove staples (use a pencil eraser to bend

open the “arms,” then gently pry it out with a letter opener), paper

clips or other metal. Remove twine or rubber bands and discard. Remove

letters from envelopes and unfold them for flat storage, but leave any

brittle papers folded—don’t force them open. Keep each letter with its

own envelope, and keep collections of correspondence together.

Remove any newspaper clippings enclosed with letters, scan or

photocopy the clipping to acid-free paper and include the copy with

original documents. Keep the original newsprint clipping in separate

storage.

One good way to store paper items is placing similar-size documents

together in archival-quality file folders or paper sleeves. You can

place the folders or sleeves flat in archival storage boxes or upright

in hanging folders. It you choose the upright option, don’t allow papers

to slump inside the folder. If you’re on a budget, you can use

office-quality hanging folders as long as the documents are first placed

inside archival-quality file folders.

Label each folder with the date and the name of the family or

individuals associated with the document. To make items easier to find,

number the folders and keep a list of what’s in each one. As you place

each paper in its folder, consider scanning it to easily preserve and

share the content.

Photos

There are many ways to organize your photos. After sorting through

the collection, decide whether to organize photos by family, date,

subject, event, place, photographer (for example, photos Mom took), size

or type of image (such as daguerreotype, tintype, etc.).

Your storage strategy depends on the type of image you have. Don’t

worry if you have difficulty determining whether your photos are

daguerreotypes, tintypes or ambrotypes. The care for any cased image is

the same: Store these in close-fitting individual photo storage

envelopes or sleeves inside an archival box. It’s important that both

the envelopes or sleeves and the box fit the photo snugly to prevent

images from sliding and scratching.

Keep prints in sleeves or envelopes made of archival-grade paper or

clear plastic. Store same-sized prints together, stacking them carefully

to avoid scratching. Place rare prints in individual sleeves. Store

these envelopes vertically in same-sized archival boxes.

Color photos are especially prone to fading when exposed to light,

but even images stored in the dark may develop “color shift” and a

yellowish haze. Fortunately, by scanning and digitally restoring old

prints, you can bring back much of the original color. Store old prints

in archival paper or plastic sleeves inside photo storage boxes. Keep

these in a cool, dry place. The cooler your keep your photos, the longer

they will last, but don’t refrigerate them or put them in the

basement—humidity causes its own problems. A shelf in an interior closet

in the living area of your home is best, and check the collection

regularly for pests.

Cataloging your keepsakes

After your demise, will your family know the importance of that odd

assortment of china you inherited from your grandmother? Or will they

(gasp!) sell your precious family treasures at a garage sale? Telling

family members the objects’ importance can’t hurt, but they might not

remember the story you’ve told about each item. Instead, make an

inventory of your family artifacts. For each keepsake, include details

such as:

- how it came into your possession

- who owned it originally

- when it was made

- what family stories are associated with the heirloom

Keep this with your important papers.

You also might want to catalog heirlooms that aren’t in your

possession, so you and future generations know family treasures’

whereabouts. You can start with the handy Heirloom Inventory and History

form (a free download), or create your own inventory from scratch. For

each item, include the relative’s name, contact information, a

description of the object, the item’s history (who owned it originally,

how it was passed down in the family, how the original owner got it) and

stories associated with it. Next, photograph the objects from different

angles and add the pictures to your inventory.

Here’s a sample from one family’s heirloom inventory:

Dark blue Stafforshire tea and

coffee set, circa 1840. Set consists of a coffeepot, teapot, creamer,

sugar bowl, and four cups and saucers. All but the sugar bowl and

creamer, purchased at a later date, belonged to the family of Emma

(Ludwig) Rhoads and were used at their farm at Yellow House, Pa. Present

owner: [name and address].

You can even inventory missing family heirlooms. Make the descriptions as complete as possible:

Unfinished and unsigned needlework

sampler, probably stitched by Ellen M. Lorah, daughter of Mary (Rhoads)

Lorah, Broomfieldville, Berks Company, Pa., who attended the Linden

Hail School for Girls in Lititz, Po., in 1860, when she was 16. Floral

decorated, about 6 ×18 inches. Current owner. unknown.

Make at least two copies of your family history inventory and any

pictures of heirlooms. Keep one copy with your genealogical files, and

store another copy with your important papers, so it will stay in the

family. If you have a family history Web site or publish a family

newsletter, you might want to post the list of family heirlooms,

especially if it includes unidentified or lost items.

Sharon DeBartolo Carmack, from the May 2004 issue of Preserving Family History.

3. Make homes for heirlooms

“Artifacts” doesn’t describe only objects excavated on an

archeological dig. Curators and collectors use the term for the many

manmade objects that acquire historical or artistic significance. For

the family historian, artifacts may assume emotional and sentimental

value, as well. Your great-grandfather’s pocket watch and your aunt’s

Depression-era quilt are examples of the kind of artifacts you might

find in your family archive.

Preserving inherited artifacts isn’t necessarily complicated,

especially if the object is on display or used in your home. Some items

need a bit of extra TLC, but most will likely be just fine with the same

care and attention you give everything else in your home. If you’ll be

storing the artifacts, take the standard precautions against extreme

temperatures, humidity and pests.

No matter what type of artifact you’re handling, always wash your

hands before touching it, and remove rings and bracelets to avoid

nicking or snagging the item. Here’s how to store various artifacts:

- Art: Museums recommend rotating displays of

valuable pieces—six months on display, six months resting in storage—to

prevent overexposure to light, dust and other environmental elements.

- China and collectibles:

Don’t wrap china in newspaper or acidic newsprint paper for long-term

storage; this can cause discoloration. Use acid-free, lignin-free tissue

instead. Keep breakables in sturdy, crush-resistant archival boxes.

- Furniture: Spray

furniture polish is convenient, but it’s a poor choice in caring for

wood. Use a clean, slightly damp cloth instead, and try to keep pieces

out of direct sunlight.

- Musical instruments:

Use a soft cloth to remove dust. Regularly playing an instrument is the

best way to monitor its function and repair needs. Without proper

maintenance, that violin or brass horn can easily lose its function to

make music and become simply another interesting artifact.

- Quilts and samplers:

Roll large fabric items, such as quilts, around an archival tube to

avoid creases. Cushion and protect the surface with archival tissue. Use

a piece of clean washed muslin longer than the roll to form a

protective outer layer: Roll the muslin around the item one and a half

times, then tuck the ends into the ends of the tube. Gently tie cotton

twill tape or muslin strips around the roll to secure.

- Clothing:

If it’s in good condition, launder clothing such as wedding dresses,

uniforms and christening gowns after use and hang to store (consult a

professional cleaner for antique or intricate items). To support the

garment, wrap wooden hangers in polyester quilt batting covered with a

muslin sleeve. Stuff archival tissue in sleeves and legs for additional

support, and place the entire garment in a muslin garment bag of the

same size as the item of clothing. Don’t use plastic or vinyl garment

bags.

- Military insignia and scouting memorabilia: Store

protected with unbleached muslin or acid-free tissue inside archival

boxes. For display, don’t use a wool backing—wool contains sulfur that

will eventually damage medals. Cotton is a better option. Keep the

display away from direct sunlight.

Just as you can scan photos and documents, you can use your digital

camera to photograph family heirlooms. The photos would be a terrific

addition to an inventory of the heirlooms in your possession (download an inventory form here).

Family archives are a great resource for family historians and a

wonderful legacy to pass on to future generations. The time you spend

organizing and preserving your archive will help you—and your

family—take full advantage of all of the genealogical information and

memories those old letters, photos and keepsakes hold.

Value Judgments for Heirlooms

What kind of value do your items have? Value is commonly understood

as something’s merit, worth or importance with regard to money, history,

culture, art or sentiment. The second half of the definition is often

unstated, but it is essential in any evaluation of value.

Monetary Value

Monetary value refers to the price an item would bring on the open

market, or its fair market value. Scarcity and condition play a large

part, as does the current popularity of the item as a collectible. An

appraiser can assess an item’s monetary value so you can have it

insured.

Monetary value often is different from intrinsic value. Your family

may place an intrinsic value of $500 on your grandmother’s crystal candy

dish—that is, you wouldn’t consider selling it for anything less. But

an appraiser may put the monetary value at $80 because it’s old but not

rare, and that’s what similar dishes sell for on eBay. This also may be

the insurance value of the candy dish and your tax deduction if you

choose to donate it.

Historical and Cultural Value

Historical and cultural value is determined by events, people and

places associated with an item. It may or may not carry a corresponding

monetary value. Your grandmother’s diary, for example, may have little

monetary value compared to its historical value as a window into the

life of a WWI Army nurse.

Even so, museums seek out and purchase items for their collections,

which helps establish the cash value for historical artifacts. The

current black market in historical and cultural items has created an

entire industry based on selling stolen and forged historical artifacts.

Artistic Value

Artistic value may be high if a piece shows skill in painting,

sculpture or other media, but not all “good” art acquires a high

monetary value. In general, the artist, school or subject matter must

already be famous. Sometimes nice paintings are just that—enjoyable

paintings of no exceptional monetary or historical value.

Sentimental Value

Sentimental value is most familiar to the family historian. Many of

us cherish “worthless” little trinkets for the memories they inspire. It

isn’t uncommon for families to haggle over who gets the cookie jar

after Grandma’s death. It’s not the thing, it’s the memories that go

with it.

Tip: Having trouble letting go of papers from

Grandma’s house? Separate items in a box and see if other family members

want anything. If no one else finds value in the papers, you may feel

easier about tossing them.

Denise Levenick blogs about organizing and preserving family archives at The Family Curator.

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2012 issue of Family Tree Magazine .