Written by Maureen A. Taylor, unless otherwise noted

ADVERTISEMENT

Ever wish you could find out what your family was doing between the decennial US census enumerations?

You can. City directories and similar listings provide a regular—usually, annual or biannual—glimpse into the everyday lives of your ancestors, from employment to residences to what they did with their leisure time. Simply put, they can put your ancestor in a time and place, making it easier to locate other genealogical records.

This guide will guide you to the directories likely to name your kin, and help you mine these listings for every possible ancestral clue. Here’s how to find and read old city directories.

Types of Directories

Names and addresses are the fundamental components of directories. Beyond that, directories may differ, with their focus on various populations, listings by house number or name, additional details about individuals, and other supplemental content. The basic types of directories of interest to genealogists are:

City directories

Similar to phone books, city directories list residents of a particular locale. (Despite the name, some also covered small towns and rural areas.) Two prominent publishers of these books, which usually came out annually or biannually for a given area, were R.L. Polk & Co., and Williams.

The first US city directories as we know them today were issued in Philadelphia in 1785 by two competing companies. Many other cities followed suit.

City directories were originally intended for businessmen to find customers, so the earliest ones may name only property owners, employed individuals (which excludes most women) or socially prominent citizens. Later directories usually list heads of households with their spouses and adult children.

Information given varies with the time and place, but generally includes

- name

- address

- occupation

- employer

- marital status

- whether he or she owns the residence, rents or boards.

The latter details are usually indicated by abbreviations such as bds (boards), rms (rooms), wid (widow) and stu (student), and shortened occupation titles such as hrnsmkr (harness maker). You also might see names abbreviated, such as Chas (Charles) or Wm (William). We provide a list of common abbreviations below, and you can look in the front or back sections of a directory for a key to other abbreviations it uses.

By the mid-19th century, directories often included supplemental local information, such as local government details; maps; guides to street-name changes and renumberings; lists of churches, clubs and organizations; categorized lists of businesses; and “criss-cross directories” with lists of residents by the street name and house number. You might even find a list of deaths with the age of the deceased, births in that year, and where former residents moved.

House directories

These handy volumes contain information similar to city directories, but they’re arranged by street and house number instead of surname—a criss-cross directory, but in its own volume. These give you a picture of each household, letting you see generations that resided together or lived near each other. You’ll get a feel for an ancestral neighborhood, from who lived there to nearby churches and businesses.

Beware of street numbering changes, which can make it appear your ancestor moved when he didn’t. Double-check addresses using city directories.

Unfortunately, separate house directories are limited, mostly to larger cities and towns. Be sure to check the back sections of city directories for criss-cross listings.

Business directories

While city and house directories may contain business information within general listings or in a separate section, business directories list only businesses. For a given area, they’re usually organized in alphabetical order, but sometimes arranged by type of business, such as jewelry manufacturing, or auto dealers.

Two caveats for researching in business directories: These aren’t available for all locations or time periods, and they may not be all-inclusive. Not all companies participated in the publication.

Trade directories

You also might find a directory of businesses in a single category that covers the entire country, such as Seeger and Guernsey’s Cyclopaedia of the Manufactures and Products of the United States (several editions of which are available free through Google Books) or Farley’s Reference Directory of Booksellers, Stationers, and Printers in the US and Canada (published since 1886; with various editions available on Internet Archive). Professional directories, which usually cover the whole country, list prominent professionals and tradespeople such as railway workers, doctors or lawyers.

Telephone directories

You can view the first phone book, dated 21 February 1878 (shortly after Alexander Graham Bell made his first successful telephone call), online at Old Telephone Books. It’s a single sheet of 50 business subscribers—with no addresses or phone numbers—to the New Haven, Conn., telephone exchange. As the number of people with phone service increased, telephone directories began to resemble their contemporary descendants.

Naturally, for your ancestor to appear in a telephone directory, he had to own a telephone. Most cities had both city directories and telephone directories until phone service became ubiquitous. Phone directories replaced city directories for the most part in the mid-20th century.

How to Find Directories

All major cities had city directories by the mid-19th century. Rural communities might be covered in directories for nearby cities, and/or in directories titled by region. The introduction of house and business directories varies with the place; you might find these combined with a city directory.

If you’re not sure whether a directory exists for the community you’re interested in, you could ask at the local library or check the state listings in the online microforms catalog from Gale (filter collections by the word Directories).

Directories are relatively easy to find on microfilm, and even better, they’re increasingly available online. Here’s how to find the ones you need.

Libraries

The main branch of the library where your ancestors lived is a great starting point for city, business and house directories from that place, whether on paper, microfilm or online. Large municipal and county libraries may have directories for nearby cities, other major cities in the state, and “feeder” regions—common places of origin for settlers of that area.

Also look for local directories at historical societies, state archives and libraries, and university libraries. Some libraries have old phone books, but they were printed on poor-quality paper and usually tossed when the next year’s edition was printed.

Directory collections at large genealogical libraries may cover cities across the United States. If you live near Washington, DC, you can use the country’s largest city directory collection at the Library of Congress.

The Family History Library in Salt Lake City also has directories. Search the online catalog by place, then look under the directories heading to see what’s available.

Don’t live near a library whose directory collection covers your ancestral hometown? You may be able to borrow directories on microfilm or microfiche via interlibrary loan. Ask your reference librarian for help making the request; it’ll cost roughly $5 to $10 per borrowed item and you’ll need to use it in your library.

City directories online

City and other directories are becoming increasingly easy to find online. A great starting point is Online Historical Directories, where genealogist Miriam Robbins categorizes links to online directories (both free and fee-based) by country, state and county. Use the Home drop-down at top right to navigate her site.

The print quality often isn’t great in these books—which, after all, were meant to be used only until the next edition came out. Optical character recognition (OCR) indexing can make it difficult to search for names on pages where the OCR software couldn’t “read” the text. When your name search doesn’t find someone who should be there, browse the pages.

Local library websites

If you’re lucky, your ancestor’s local library will have digitized city directories—look for a link to If you’re lucky, your ancestor’s local library will have digitized city directories—look for a link to genealogy databases or digital resources. Scrolling the alphabetical listings is a good idea no matter where you find your digital directory.

Ancestry

Ancestry.com has a huge collection of digitized city directories. Its collection “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995” has more than 1.5 billion records.

Because Ancestry.com has many collections that include city directories, hit them all at once by searching the City and Area Directories collection. Searching the Professional and Organizational Directories category will help you find people in business and professional directories.

Perhaps because of the size of the collection, many people think that if the directory isn’t on Ancestry.com, it doesn’t exist. Yes, Ancestry’s collection is enormous, but it doesn’t have everything. Though Ancestry.com’s collection of city directories is massive, it doesn’t include all of the ones that have been published. The local public library and other websites can help you fill in the gaps.

MyHeritage

Search the Compilation of Published Sources on MyHeritage, which contains a variety of types of books in addition to city directories. The site also has a huge dedicated collection of US directories.

Internet Archive

Besides hosting the Wayback Machine, Internet Archive has digitized millions of items, including city and county directories. To find them, begin with a basic search of city directory or county directory (For example, Indianapolis city directory or Nassau county directory.)

Google Books

Use the same search strategy that you would on Internet Archive. However, be aware that some results may only be a snippet or preview of the full directory.

WorldCat

If the local public library doesn’t have the directory you need and you can’t find it digitized online, look it up in WorldCat to see what other libraries have it.

Portions of this section written by Amy Johnson Crow

12 Ways to Use City Directories

Working backward a year at a time, check directories for each year your ancestor lived. Keep track of each mention of him or her, the details of the listing, and the source of the information in the sheet on the last page of this workbook. You’ll be creating a timeline for their lives and sorting out clues you can use to.

Read on for some ways you can use city directories.

1. Find more records

Directories are full of clues to direct you to additional records. When a woman suddenly appears in a directory as a widow, you’ve narrowed the window for her husband’s death. The employer or occupation could direct you to occupational records, or at least let you learn more about the work a person did. A notation that the person owned his home will send you to research deed records in the county. The first date an immigrant ancestor appears in a directory could be a useful clue when looking for naturalization records. If you’re looking for church, synagogue or religious school records, start with churches of your ancestor’s religion that were near his residence.

Finally, the address, occupation and other details can help you identify the right person in other genealogical records.

2. Fill in blanks

In areas and times where decennial US census records are missing—including virtually the entire enumeration for 1890—city directories can serve as a substitute source. Once you have a good idea of the place your ancestor lived during the census, check city directories for those areas. Unsure where the person lived? Try searching large databases of directories, such as Ancestry.com’s.

3. Browse the census

If your problem isn’t missing census records but instead an ancestor missing from the US census, find his address in the city directory published nearest to that census. Then use the address to determine the census enumeration district and browse records for that district.

4. Track movements

A sudden appearance or disappearance tells you a person moved in or out, or died (although it could take new residents a couple of years to be listed in a directory). If a young woman goes missing from her parents’ household, try looking for her in marriage records. Creating a timeline of a person’s appearances in city directories and other records can help you track confusing migrations, separate same-named individuals and solve other research brick walls.

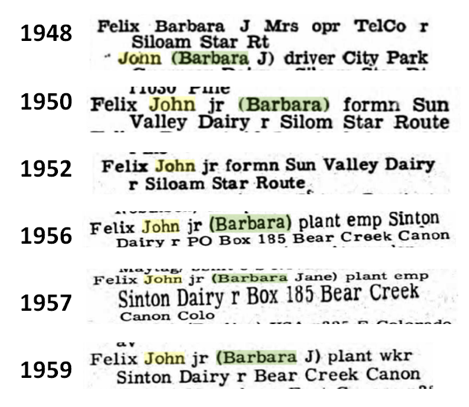

Example: I often use city directories to track my relatives’ lives from year to year. I can see subtle (and occasionally dramatic) changes in the household. These events are not captured by censuses taken only every 10 years. For example, the life of the young WWII veteran John Felix unfolds in Pueblo city directories in the years following that 1945 entry:

As you can see, by 1948, John’s a married man. He and my grandmother Barbara are both in the workforce. She’s a telephone operator and he’s a driver. Within two years, Barbara has become a stay-at-home mother and John is a foreman at the Sun Valley Dairy, a position he still holds in the 1952 directory. By 1956, he has taken a job at the Sinton Dairy, and the family has moved from Siloam to Bear Creek Canyon. The next three years see him holding steady as a plant employee at Sinton.

Example written by Sunny Morton

5. Establish family groups

Same-surnamed individuals listed at the same address are likely related—just don’t assume it’s always a parent-child or a sibling relationship; a cousin or daughter-in-law may have moved in. Also consider that folks with the same last name who work for the same employer or live next door could be relatives. Note that MyHeritage’s directories allow you to easily view who else lived at an address.

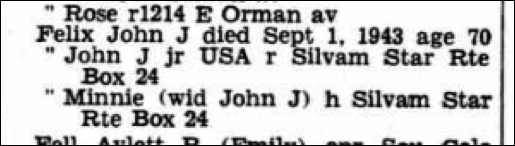

Example: The residential listings in city directories may include your ancestors’ address; names of adults and their occupations. In addition, they’ll reveal whether they rented, owned or boarded at their residence; and their addresses. Occasionally other gems appear, too. Take a look at this listing for my grandfather and great-grandparents in the 1945 Pueblo, Colorado city directory.

This entry, digitized on Ancestry.com, shows my great-grandfather’s death date and age at death. His son, my grandfather, is listed beneath him. His occupation as “USA” hints at his recent release from WWII military service. Next appears my great-grandmother, identified as the widow of John J. It’s a sad but powerful snapshot of my family just after the war.

Example written by Sunny Morton

6. Map the neighborhood

Use cross directories or house directories in combination with an old map to get a picture of your ancestor’s street and who the neighbors were. In city or business directories, look up your ancestor’s employer, church, school, social clubs and other organizations he patronized. You can use Google Earth to plot the residences and other places you discover, creating a visual reference for your research.

7. Date mystery photos

Do you have an old photo with a photographer’s imprint? These imprints usually provide the studio name and address, so you can look it up in consecutive city or business directories. Once you know what years the studio operated, you’ll have a date range for your photo.

8. Research house history

You can also use directories to research houses. Look up an ancestral address in house directories (or the criss-cross listings in city directories) to identify previous and subsequent owners of your ancestor’s house.

Example: Here’s how expert cartographer Randy Majors does this. I especially love how, once he discovered that a street name changed, he used entries for the neighbors to determine the previous name of the street and trace its occupancy back to around the time it was built.

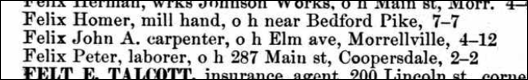

I like to browse each year of a city directory in which my ancestor appears to see what else I can learn. Sometimes I’ll find listings for the family’s places of employment. I can see how far away they worked from home. I may find listings for a relative’s church or school, or the names of cemeteries or funeral homes that served the family. In the 1889 city directory for Johnstown, Pennsylvania, I discovered the stunning tale of my Felix ancestors in the Great Johnstown Flood: the great-grandpa whose death was listed in the 1945 directory above was a teenager at the time. Watch that below.

The Ancestry.com city directory listing for the family reveals that the entire family survived. They took in flood survivors, tripling the size of their household (that’s what the number “4-12” means at the end of the Felix listing, as explained in the front of the directory).

Another part of the directory tells the story of the flood, down to details about how each neighborhood fared, including the Felix’ part of town.

Example written by Sunny Morton

9. Trace businesses

If your ancestor was a business owner, directories can help you determine the type of business and the years it operated (perhaps pointing you to records such as permits, licenses and manufacturing censuses). You might even find an old advertisement for his company.

10. Learn about street name changes

Many urban areas have changed street names and renumbered addresses over the years, as Chicago did in 1909 and 1911, and Cincinnati did in 1897 and 1918. You’ll usually find the changes explained in city or house directories published soon after the change took effect.

11. Find local newspapers

Directories might also list some of the newspapers published in the area, helping you identify additional resources.

12. Locate living relatives

Use recent directories such as telephone books and online address listings to find other descendants of your ancestors—a path to family information and photos that didn’t travel down your line.

Substitutes for City Directories

If you can’t find directories for a particular area, try substituting tax records, which were usually also recorded annually. They probably won’t contain all the information in a directory, but you can find them for consecutive years to estimate when an ancestor lived in a certain town.

Common Abbreviations in City Directories

| • b or bds: boards, boarder • bkpr: bookkeeper • c or cor: corner • carp: carpenter • ch: church • clk: clerk • col or col’d: colored • dom: domestic (often used for a housewife) • fcty: factory • gro: grocer • h: house, householder | • lab: laborer • mdse: merchandise • mer: merchant • mkr: maker • nec: northeast corner • nwc: northwest corner • phys: physician • prop: proprietor • r: rents, rooms, resides | • res: resides • sch: school • off: office • own: owns, owner • sec: southeast corner • swc: southwest corner • t: tenant • wid: widow • wkr, wks: worker, works |

Example: How to Read a City Directory

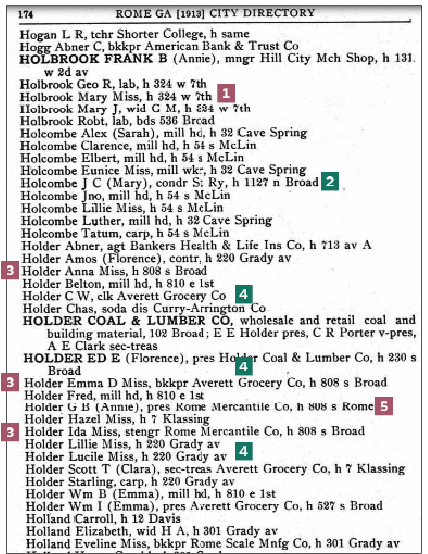

Directories usually came out every year or two. The format and contents vary by location, time period and publisher. Most directories list people by surname; some are arranged by address or have a “cross listing” by street in the back. Residents may be listed separately from businesses and organizations, or combined, as in the 1913 directory from Rome, Ga., below. In some places, primarily in the South before 1960, African-Americans were listed in a separate section. You’ll also see businesses’ ads.

When using a city directory, review the table of contents and introductory text to understand the organization, format and abbreviations in the book.

Individual listings often give a person’s occupation in abbreviated form, sometimes with the type of business or employer’s name. A married man’s name may be followed by his wife’s name in parentheses. Other notations may indicate a single woman or a widow. If a widow appears at the same address where the husband lived in the previous year’s directory, you’ve narrowed his date of death.

Searching a chronological run of annual city directories can help you estimate when a family arrived in an area. Use old maps to locate the place of employment, as well as nearby churches and schools the person may have attended.

1. “Miss” might follow the name of a single woman. Widows may be noted with “w” or “wid,” and some directories include the name or initials of the deceased spouse. Here, a single Mary Holbrook resides at the same address as Mary J. Holbrook, the widow of G.M. Holbrook, and Geo. R. Holbrook, a laborer (lab). It’s a strong possibility they’re related, perhaps a mother and her children.

2. This directory gives a man’s occupation and employer’s name. J.C. Holcombe, whose wife’s name is Mary, is a conductor for the Southern Railway (condr S: Ry). Check the front of the book for a key to abbreviations.

3. Check all the listings for a surname. Those living at the same address are usually related. Miss Anna Holder, Miss Emma Holder and Miss Ida Holder all live at 808 S. Broad. The address can help you locate hard-to-find folks in censuses; 1880 and later censuses give each person’s relationship to the head of the household.

4. Persons with the same surname and employer may be related. Emma D. Holder is a bookkeeper for the Averett Grocery Co. William I. Holder is the president of that company, Scott T. Holder is secretary-treasurer, and C.W. Holder is a clerk there. Scott T. Holder and his wife (Clara) live at 7 Klassing, as does Miss Hazel Holder, suggesting she’s a daughter.

5. Watch for errors. The address given for G. B. Holder and his wife, Annie, is 808 S. Rome. Misses Anna, Emma and Ida Holder are listed as living at 808 S. Broad, and both Ida and G. B. work for the Rome Mercantile Co. So there’s a strong reason to believe that G. B. and Annie are the parents of the three single women, and that all five live in the same household. Other records indeed confirm the family lives at 808 S. Broad; the city directory’s 808 S. Rome listing is an error.

Written by George Morgan, from the December 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine

Resources for Finding and Using Directories

Websites

- Ancestry.com: City & Area Directories

- City Directories of the United States

- Cyndi’s List: Directories

- FamilySearch Wiki: US Directories

- Fold3.com: City Directories

- Google Books

- Internet Archive

- Library of Congress: 1997 Inventory of Criss-Cross Directories

- Library of Congress: Telephone and City Directories

- MyHeritage: City Directories

- Online Directories Site

- Rootsweb: Directories

Books and Publications

- Bibliography of American Directories Through 1860 by Dorothea Spear (American Antiquarian Society)

- City Directories of the United States (Research Publications)

- City Directories of the United States, 1860–1901: Guide to the Microfilm Collection (Research Publications)

- Guide to American Business Directories by Marjorie V. Davis (Public Affairs Press)

Directories Fast Facts

Coverage: Most large urban centers; time varies, with the earliest in the United States in 1785 (Philadelphia) and widespread adoption by the mid-1800s

Location: Printed copies for the local area are available in many public libraries, which may have microfilm copies available through interlibrary loan. The Library of Congress, Ancestry.com and MyHeritage have the largest collections of US directories.

Key details: Names of adults or employees in area/profession; names of businesses; addresses of people and places; occupations/employment information; marital status

Search terms: Enter name of city plus city directory, house directory or telephone book; or name of trade plus trade directory.

How to find in the FamilySearch catalog: Run a place search for the county or town, then look under the directories heading.

Alternate and substitute records: tax lists, state and federal censuses, voter registrations

Versions of this article appeared in the December 2013, December 2014 and May/June 2022 issues of Family Tree Magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment