Genealogists love to commiserate about the brick walls blocking their backward march into their families’ pasts. Often these brick walls turn out to be merely detours that you can find your way around with a fresh look, different records or some sideways or “cluster” research. Other times, your brick wall proves to be a genuine dead end. After all, every family history reaches a point where you can go no further—otherwise we’d all be connected to Adam and Eve, or at least to Cleopatra and Caesar.

How can you tell when you’ve really hit the end of the road and it’s time to stop beating your head against a brick wall? Just how far back do historical family records go, anyway?

The answers depend on the nature of your brick wall and why you can’t seem to make progress in this branch of your family tree. Let’s look at 10 possible ultimate brick walls, in roughly increasing order of finality, and find some potential paths around them.

1. You’ve run out of online records.

A few years ago, it would’ve seemed silly to list this as a brick wall. But we’ve come to expect an abundance of online records, and this convenient access has drawn even the most time-crunched people into genealogy. So it might feel like a brick wall when you can’t continue tracing your tree at home in your pajamas. But even though Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org and other sites have millions of historical records, many more millions are offline, on microfilm or paper at repositories. Exhausting what’s available on the internet isn’t a genuine dead end. Use online library catalogs and research guides to point you to resources you can access by visiting libraries, courthouses, archives and even cemeteries not yet cataloged on Find A Grave.

2. The records you need aren’t (yet) available to the public.

Privacy concerns protect certain vital records (depending on the state), and the 1950 US federal census won’t be released until April 1, 2022. Patience is a virtue in this case, but you may not be willing or able to wait years or even decades to discover ancestral details. Other records, such as medical or certain military records, may never be available to the public, and your connection to the individual may not be close enough to get them released to you.

This could indeed spell the end of the trail, but it’s too soon to give up. First, find out about any hoops you could jump through, such as proving a relationship to the person named in the record or petitioning a court to open the records. For relatively recent ancestors, for whom censuses aren’t available and whose vital records are probably still under restriction, substitute sources such as city directories, phone books, newspapers, and tax and voting lists.

Ancestry.com even has a 1950 census substitute search page if you can’t wait until 2022. Church records, obituaries and probate records may help replace unavailable vital records. Find city directories on sites such as Fold3 and church records and probate records on FamilySearch.org, Ancestry.com and AmericanAncestors.org.

3. You face maiden and other name mysteries.

Sometimes, you simply can’t find the name you need to keep following a branch of your family tree. This is of course common with those elusive maiden names, but may also occur when any ancestor’s parentage remains stubbornly unknown or unprovable. You might even suspect an ancestor’s identity but can’t put the pieces together, or can’t tease out your ancestor with a common name from a welter of same-name individuals.

It’s possible that such mysteries will never be solved, but that doesn’t mean you should give up. Try all the time-tested tricks and advice about overcoming brick walls. Land, court and church records can be especially helpful in solving maiden-name and parentage puzzles. Some of these records are available on FamilySearch.org, Ancestry.com and Findmypast. Many US land records are available at the Bureau of Land Management. Researching the ancestor’s siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, neighbors and other associates is another effective strategy.

Still stumped? Set the problem aside for awhile—a fresh perspective might yet find the answer.

4. The records you need have been destroyed.

This is probably the most common cause of a true dead end, and the issue need not lie very far back in the past. If you need military records to make your case, for example, it might be crushing to learn that a 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, a branch of the National Archives, destroyed approximately 16 to 18 million 20th-century military personnel files. Losses included most records of Army personnel discharged from Nov. 1, 1912, to Jan. 1, 1960, and Air Force personnel with names alphabetically after “Hubbard, James E.” discharged from Sept. 25, 1947, to Jan. 1, 1964. Read more about the 1973 National Archives fire and research workarounds.

The aftermath of a fire also destroyed most of the 1890 US federal census in 1921. The only surviving fragments cover a few areas of Alabama, District of Columbia, Georgia, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota and Texas. Many substitutes for the lost 1890 Census have been developed, though of course none can completely replace the actual census. You also can work around this gap using the 1880 and 1900 censuses, although sometimes the answers you need can be found in only 1890. State censuses taken between 1880 and 1900, or city directories, also can help fill in the gap.

A separate 1890 enumeration of Union veterans was spared. But there’s a cruel twist: Nearly all of those schedules for the states of Alabama through Kansas and approximately half of those for Kentucky were destroyed prior to transferring them to the National Archives in 1943. (Fragments for some of these states were accessioned by the National Archives as bundle 198.) You can search the remaining schedules at FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com.

Another famous series of losses affects Irish census records: The original census returns for 1861 and 1871 were destroyed shortly after they were taken. Censuses for 1881 and 1891 were pulped during World War I, likely due to paper shortages. Worst of all, the returns for 1821, 1831, 1841 and 1851 were mostly destroyed in a 1922 fire at the Public Record Office. Read tips on working around these destroyed Irish census records.

Aside from such large-scale destruction, the most common problem encountered in US research is “burned courthouses.” Many early courthouses, especially in the South, were made of wood, and when they went up in flames, so did the records they held. Before despairing, investigate whether the records (or copies) might have been transferred to a state archive, and make sure you’re looking in the right place: Changing county boundaries often meant older records remained in the parent county, where perhaps they survive.

In Europe, the long history of wars has taken a toll on records as well as the populations they recorded. Nations relatively unscathed by war since the beginning of modern record-keeping, such as those in Scandinavia, are most likely to have intact records stretching back centuries. In other countries, such as present-day Germany, record loss may be spotty; here, too, copies of destroyed records may still exist in regional archives or diocese or archdiocese repositories. Blame the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) for the loss of most pre-1650 German records.

Eastern European records generally fared the worst in wars as well as from Nazi and Soviet occupation. The ever-changing map of this part of Europe may hold out hope, however, as the records you need might have been created when your ancestors’ village was actually part of a different country than where it lies today and might still be in an archive there.

In short, make sure that the records you need have really been destroyed and you’ve exhausted all possible workarounds before throwing in the towel.

5. The specific records you need were never created in the first place.

Many beginning family historians are shocked to find how relatively recently many jurisdictions, especially in the American South, started keeping vital records. Even the US federal census, begun in 1790, leaves more than 180 years of colonial populations since Jamestown unenumerated. Other countries can prove even more frustrating: Italy didn’t get around to taking a census until 1871, for example, and the enumerations before 1911 aren’t very useful.

Much as with records that have been destroyed, you can often find substitutes. Tax lists and colonial censuses can stand in for early enumerations. Church records typically pick up where government vital records leave off. Start your workaround to check for these records on sites such as FamilySearch.org, Ancestry.com, AmericanAncestors.org and Findmypast.

Native American ancestors are a special case for whom many of the records we take for granted were never created until the reservation era. See our guide for tips on researching Native Americans in your family tree.

The question of exactly when record-keeping of any sort began for your ancestral area does come up—and we’ll explore in depth below.

6. The only “records” you can find are compiled genealogies.

Although we’re constantly warning in these pages about the perils of assuming someone else’s research is correct, sometimes you reach a point where that’s all you can find about your ancestors. Colonial kin, for example, may be traced in compiled genealogies available in libraries or online. Some of these are notorious for errors repeated as fact, such as the genealogies of southern families cranked out by John Bennett Boddie from the 1930s through the 1960s.

You already know you should use these “facts” as clues to prove with original records. But what happens when the records run out and such secondhand compilations are all you can find? While continuing your quest for hard evidence, you may have to accept that you’ve hit a brick wall of sorts. Such secondhand pedigrees are (probably) better than nothing, so at that point go ahead and cautiously make use of them.

7. You’ve run out of American records.

A cruel sort of brick wall comes when the trail on this side of the Atlantic goes cold and you have yet to “jump the pond” back to records in the old country. Immigration records and passenger lists can sometimes enable you to skip over your ancestors’ earliest American presence and start researching abroad. But these often don’t prove detailed enough to pick up the trail in your ancestors’ homelands, where you’ll need to know a specific parish or village of origin.

Home sources such as letters, family papers and Bibles may help you break through. If you’ve exhausted all the resources of your own family, check with cousins. I once peppered my second cousin with so many questions about our mutual ancestors that she finally shrugged and said, “I might as well just send you the family Bible.” In the pages of that Bible I didn’t know existed was the scribbled name of the parish in Sweden I needed to jump-start my stalled research.

Failing such a breakthrough, just because you can’t find any more US records doesn’t mean answers don’t exist abroad. Give FamilySearch.org and its ever-growing collection of global online records a shot—especially those databases you can search by name rather than browse (which requires narrowing down by dates and places). In countries with databases that can be searched without knowing a specific locality, try some best guesses and see if you get lucky. Examples include the subscription site Findmypast for the British Isles, ScotlandsPeople, the Norwegian archives, the Netherlands’ Wie Was Wie (“Who Was Who”), and Denmark’s Demographic Database and Digital Danish Emigration Archives. If your ancestors left records on the other side of the Atlantic, you ought to be able to find them with perseverance and luck.

A special case of reaching the end of the trail in America, of course, is researching enslaved ancestors. While this may indeed present an insurmountable brick wall, see the January/February 2015 Family Tree Magazine and our guides on African-American genealogy for help.

8. You’ve reached the end of written records—at least for commoners.

As much progress as I’ve made with my Swedish ancestors, I know eventually I’ll hit an insurmountable brick wall. Swedish church records—the oldest records generally kept for that country—were first mandated in 1688, although some parishes began keeping them as early as 1622. The oldest Swedish genealogical record of any sort is a letter from Ingeborg Jonsdotter about a donation of land to the church in 1308.

For many European ancestries, widespread recordkeeping of use to genealogists began with the Council of Trent’s 1563 decree that Catholic priests should note baptisms, marriages and deaths in their parishes. This rule was widely ignored, however, requiring a papal reminder in 1595. Again, some places were early adopters; the earliest known Spanish church records date from 1307, and many Spanish parishes have records prior to and shortly after 1500. In England, the earliest surviving series of public records are called the pipe rolls (after their resemblance to pipes when rolled up) of the exchequer, accounts of royal income and taxpayers initially kept by sheriffs. The oldest date from 1129 and 1130, with continuous records from 1155 to 1832. Many have been published and indexed by the Pipe Roll Society.

An even earlier one-time enumeration is the famous Domesday Book, commissioned in 1085 by William the Conqueror. It covers landholders in 13,418 English settlements south of what was then the Scottish border.

Even the most fortunate research into European ancestries of non-nobility will reach an ultimate roadblock at the beginning of written records. If you’ve traced your English family tree back to a landholder in the Domesday Book, you can congratulate yourself on a job well done and move on to another branch.

Those with ancestors elsewhere just might get extremely lucky and do even better. On PBS’ “Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates Jr.,” celebrity chef Ming Tsai’s ancestors were on the only still-standing stone record (stele) in his ancestors’ part of China. Using that data and ancient books, the program’s researchers traced his family tree to his 116th-great-grandfather in the 27th century BC.

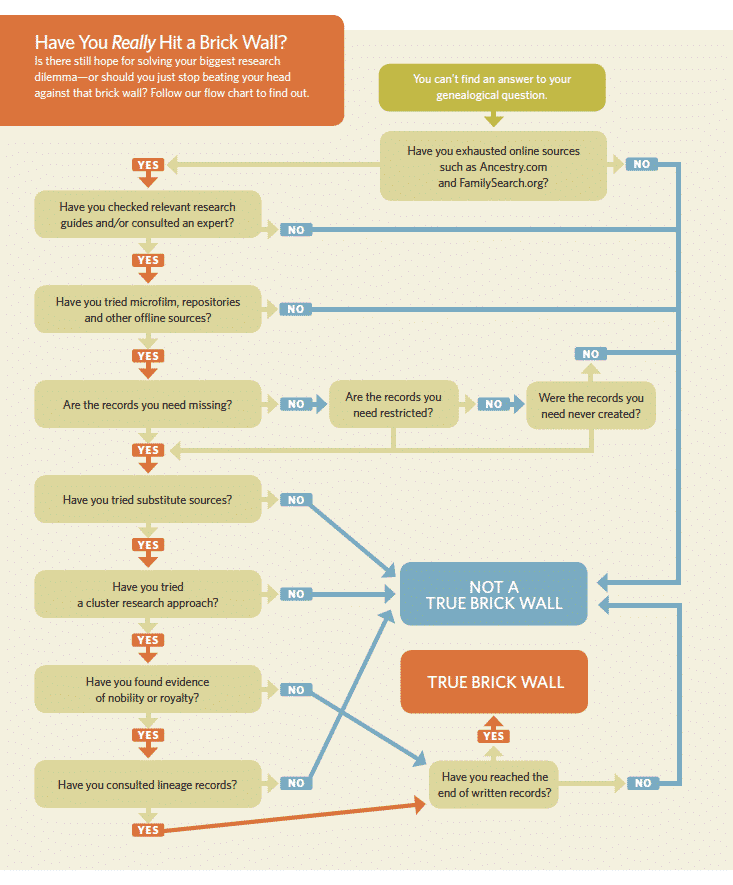

Use our flowchart to decide if you’re really at a brick wall.

9. You’ve exhausted records of your noble or royal ancestors.

This truly is the end of the line, but it can take you back a very long way. Genealogical record-keeping of royalty is how many people trace their trees back to Charlemagne (747-814); there is even a US society of Charlemagne descendants. If you can connect to Charlemagne, that Frankish king’s proven ancestors will actually take you back to at least Arnulf of Metz, born in 582. Similarly, a project tracing the ancestors of England’s King Henry II (1133-1189) goes all the way back to Fergus, king of Dál Riata, in the fifth century.

Even if you don’t have royal roots, a noble ancestor can connect you to recorded lineages much earlier than the written records of common folk. For English nobility, the most reliable source is George Edward Cokayne’s Complete Peerage, several versions of which are available online. It traces some lines as early as the 13th century. The better-known Burke’s Peerage, with 107 editions beginning in 1826, is online in subscription form. Read more about Medieval English genealogy research.

Other countries have their own noble lineages. German nobility, for example, generally began in the eighth and ninth centuries. It’s unclear, however, how often these titles were handed down by virtue of inheritance rather than at the discretion of a sovereign, at least before the 11th century.

In Asia, too, some of the oldest family trees rely on royal roots. The Japanese emperor’s family claims to descend from a line dating to at least 660 BC, though this genealogy may incorporate legend along with fact. The royalty of Malaysia was said to descend from Alexander the Great, who invaded India in 326 BC.

In April 2015, Guinness World Records confirmed the genealogy of Confucius (551-479 BC), with 2 million descendants, as the “world’s longest family tree.” Royalty helped reach the record, as the Chinese sage was a descendant of King Tang, born about 1675 BC. (Apparently the Guinness folks missed the Ming Tsai episode of “Finding Your Roots.”)

Wherever your ancestors come from, if you’ve exhausted their records in noble and royal genealogies, you’ve definitely hit a brick wall. It’s OK to move on to another line—no one can call you a quitter.

10. You’ve reached the “begats.”

Of course, there’s one other possibility for extending your ancestry even further back in time, if you’re a believer in the literal truth of the Bible. In 1 Chronicles, the genealogical “begats” list a lineage for Hebrew peoples all the way back to Adam and Eve. If you could prove a connection to a Biblical person, theoretically you could follow the “begats” to the beginning. How far back would that be? The Bible’s internal chronology places the patriarch Abraham at about 2000 BC, and Adam is said to be Abraham’s sixth-great-grandfather. But because the Bible also has the early descendants of Adam living hundreds of years, the begats go back quite a ways. In the mid-1600s, Bishop James Ussher famously calculated that Creation began around 6 p.m. on Oct. 22, 4004 BC, putting Adam’s creation a few days later.

Now that’s a brick wall.

Tip: Can’t find an ancestor? Try looking for other relatives who lived in the same place. Their records may name your ancestors.

Tip: Even if you discover you’re not at a “true” brick wall, it’s fine to put the problem aside for awhile. This might give you a fresh perspective—or time for new resources to come to light.

From the December 2015 Family Tree Magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment