In the past, women appeared in records with far less frequency than men, especially under their own names (rather than their husbands’). If you don’t already know who they married, it’s easy to lose track of women before or after their surnames changed. For these reasons, it often takes extra effort to identify and trace women throughout their entire lives. Try these 5 tasks to get to know the females on your family tree.

1. Interview a female relative

Request some time from an older woman in your family (mother, grandmother, aunt or sister) to sit down and chat about their lives, experiences and memories. If you can do this in-person, you’ll likely have a more meaningful experience. But if you need to talk via Skype or Google Hangouts, you can use software such as SnagIt to audio- or video-record the conversation.

Before the interview, share with your subject the topics you hope to discuss, and give her veto power over any she doesn’t want to talk about. Ask her if there’s anything (or anyone) she’d especially like to tell you about. Get permission to record the conversation for family history purposes. Express your willingness to turn off the recorder if there’s something she wants to say off-the-record (and then stick to your commitment).

A lot of things have changed in women’s lives in recent decades. Don’t forget to ask your female relative about the changes that have affected her the most—and what she thinks of them. You might also ask what she thinks has not changed, for the better or the worst. Listen carefully to her perspective and don’t judge her or try to get her to change her way of thinking. This is a time to appreciate her for who she is. Thank her sincerely for sharing her thoughts and feelings, whether you agree with them or not. Here are some additional tips on interviewing a relative.

2. Find your female ancestors in all available records

Especially as you go back further in time, information about the women in your family may be buried in records about the men. Dig into documents about the husband, siblings (especially brothers), parents and children. Look for her unknown surnames in relatives’ obituaries, her marriage record(s) and her children’s birth records (find more strategies here for learning a woman’s maiden name).

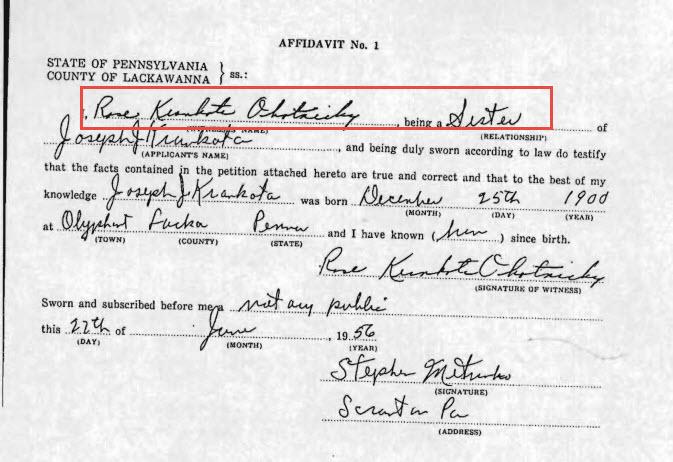

In older times, you may have to look even harder for women. Especially in the South, you may find brides mentioned in marriage bonds or the dower release portion of a land record. See if she appears as a widow in her husband’s military pension records. I once confirmed the identity of a woman by finding her mentioned in her brother’s delayed birth record, shown below (read about that here.)

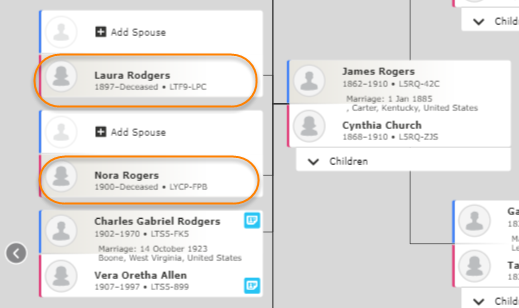

3. Tease apart multiple marriages and identify step relationships

Try to be accurate and precise about the marriages and family groups on your tree. Wherever possible, follow clues indicating that a parent is actually a step-parent; that a mother has more children you’ve already accounted for; or that someone was previously or subsequently married to someone else. Try to learn what you can about earlier or later marriages, including whether they ended by the partner’s death, divorce or bigamy.

Remember that when you attach records to individuals in your online trees, the sites may automatically attach children to step-parents who may appear as parents in census records. Untangle any mistakes that have been made by removing or clarifying relationships on your trees.

4. Follow all the daughters into adulthood

Your great-aunts and cousins deserve more than to be left dangling on a family tree with no further information than what you attach to their childhood census records. While you may understandably not want to put the same kind of effort into fully reconstructing the lives of collateral kin, try to at least account for them later in life.

Did they marry? Move away or stay local? How and when did they die? Note what you’ve learned on their tree profiles. What you learn may affect your understanding of the ancestors you care most about. Learning that your great-grandma’s little sister became a Catholic nun or that her older sister helped raise her after their mama died certainly tells you more about that great-grandma, as well. You may come to recognize patterns, too:

“Researching family and friends can reveal patterns that you won’t notice if you keep a narrow focus only on your direct ancestors. Naming patterns or physical traits might emerge, such as several members of the family being left-handed or sharing an eye color. Other patterns might include occupations, military service, religion, or even reveal social status, class or education level.”

–Vanessa Wieland in “Cluster and Collateral Research to Find Ancestors”

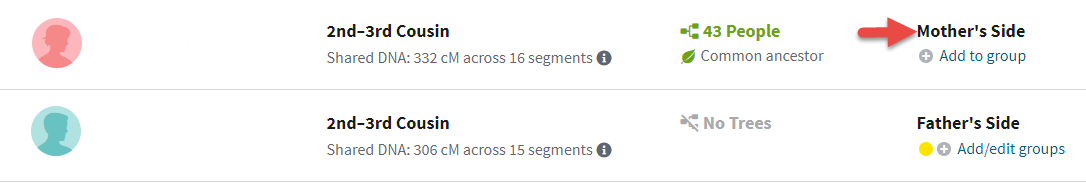

5. Pay attention to maternal DNA

If you’ve taken an autosomal DNA test, sort your matches to learn more about mom’s side of the family. In AncestryDNA’s updated Matching experience, you can now see whether someone matches you on your mother’s or father’s side (assuming it has been identified):

You can also take an mtDNA test to learn more about your direct maternal line. “Because we all have our mother’s mtDNA, anyone can take an mtDNA test to learn about maternal-line origins—and sometimes about family history,” writes Diahan Southard in this article. “Your origins information is provided in the form of an mtDNA haplogroup assignment. This is just a set of letters and numbers, such as H1a1a2b, that describes where your ancestor may have been thousands of years ago. You also get a list of people who have the same mtDNA profile as you do. Unlike autosomal DNA matches, your mtDNA matches don’t necessarily share a recent ancestor with you. Because mtDNA rarely mutates, there’s no good way to tell if a match is your second cousin or your 22nd cousin.”

If you test early enough in March, you may have your results back by Mother’s Day. (Family Tree DNA, the only major vendor of mtDNA testing for genealogy, requires 6-8 weeks to process your test.)

No comments:

Post a Comment