Legal adoption by loving new parents wasn’t common until the past century or so. Before that, orphaned American children may have been taken in by relatives or neighbors, bound into servitude, sent to orphanages or even shipped far away on a train. When children lost even one parent, they were vulnerable to being placed in new homes. Their fates depended largely on the time period and luck.

So how can you determine what may have happened to the families of children who suddenly show up on (or disappear from) your family tree? Here are five possible scenarios for what happened—and the paperwork that may help you piece together the stories.

Taken In By Other Family

It’s a timeless practice for relatives, friends or neighbors to care for orphaned children. But laws and attitudes about this practice—even what it meant to be orphaned—have changed over time. From colonial times to the mid-1800s, children were legally considered orphans if just their father had died. So a child referred to in legal documents as an orphan may have had a living mother. She, however, had few legal rights over her children or their property.

When a family of means lost its father, courts typically appointed a legal guardian to watch over the children’s inheritance until they came of age. The guardian was usually the child’s closest male relative who wouldn’t personally benefit if something happened to the child. Children often remained under the daily care of their mother, if she was alive and the estate provided sufficiently for the family. Look for records of guardianship appointments and related surety bonds in the county court that had jurisdiction, such as the county, orphan’s or probate court (the FamilySearch wiki article on that county may describe court jurisdictions). FamilySearch may have microfilmed records; search the catalog by place, adding the keyword guardian. Otherwise, contact the court directly.

If neither able-bodied mother nor family fortune existed, then family, friends or neighbors often stepped in. This wouldn’t have generated formal adoption paperwork. Evidence of their caregiving might appear in a census listing showing the child living with a new family, in correspondence, or in the child’s inclusion in the new parents’ wills or estate paperwork.

Labor Contracts and Apprenticeships

When no relatives or friends stepped forward, communities took over the care of orphans. This often was also the case for children whose mothers couldn’t adequately support them and whose fathers were unknown or absent. Taxpayers expected even young children who became public charges to work to earn their keep. A common solution from colonial times until after the Civil War was to “bind out” children into labor contracts until they reached adulthood.

Indenturing and apprenticing children could be both voluntary and involuntary. Two-parent families often willingly contracted their child’s labor to a master for a proscribed time. In exchange, the child received room, board and—for apprentices—vocational training. When the contract was up, the master provided “freedom dues,” often in the form of cash, clothing and tools.

Local officials could force children who became public charges, or who were at risk of becoming so because of poverty or illegitimacy, into indentures and apprenticeships. In the 1700s and early 1800s, elected overseers or superintendents of the poor in townships, cities or counties often made these decisions. They recorded their activities in county commissioners’ records or in separate account or logbooks. Surviving records may be in government offices or archives. Search for microfilmed records in the FamilySearch catalog by place, then look for a poorhouses, poor law or similar category. In Colonial Virginia, Anglican vestrymen documented binding-outs in parish minutes; start your search for surviving records at the Library of Virginia.

Binding-out and apprenticeship contracts were filed in local courts that had jurisdiction over orphans and estates. Contracts might name the indentured party, master and terms of the agreement. Later court records may show the conclusion, extension or breaking of the contract. Locate these records in the same way suggested for guardianships. Apprenticeship and binding-out records aren’t often found online, but Ancestry.com has a database of about 8,000 such names for Virginia.

African-American children were disproportionately impacted by the binding-out system. Before the Civil War, some Southern states allowed courts wide latitude to bind out free black children to white masters. After the Civil War, Southern states enacted new laws that favored indenturing children of color to white masters, with preference given to their former slaveholders. Justifications for indentures included parental neglect, poverty, unemployment or an act of bad behavior by at least one parent.

Binding-out contracts should first appear in local court records, along with follow-up efforts by parents to reclaim their children. After emancipation, when courts turned a deaf ear, thousands of African-American parents enlisted help from the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands (“Freedmen’s Bureau”). Start with its field office reports for information about labor contracts and disputes.

More than 1.8 million Freedmen’s Bureau records are newly indexed. Search them at DiscoverFreedmen.org or among more than 125 related databases at FamilySearch. Ancestry has a database of field office reports for multiple states. Find a directory to scattered indexes of labor contracts at The Freedmen’s Bureau Online.

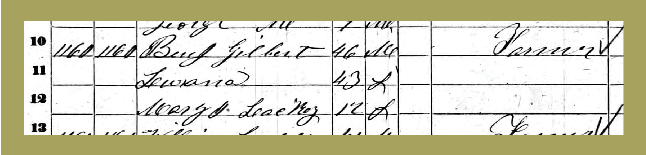

Case Study: Mary Lackey

She appeared out of nowhere. In the 1860 US census, 12-year-old Mary Lackey lives in the North Carolina household of Benjamin and Luranna Gilbert. Like all censuses before 1880, the record doesn’t state any relationship between household members. The 1850 census is no help, either: That year, the Gilberts were a childless couple in their 30s.

Who, then, was Mary Lackey?

Court records have the answer. On the 14th of April, 1851, the Yancey County, NC, Court of Common Pleas entered this order: “Ordered by Court that … Mary Lacky aged about one years old … minor heir of Elizabeth Lacky be bound unto Benjamin Gilbert until she attain to the age of 18 years … .”

So Mary Lackey was the Gilbert’s young servant. She was just one year old when she was contractually bound to them.

Orphanages and Children’s Homes

Almshouses existed in colonial America as early as the 1650s in New York, 1662 in Boston and 1702 in Philadelphia. Poor farms and poorhouses became more numerous by the early 1800s, particularly in cities. These served primarily widows and children. During the following decades, most counties established separate children’s homes. Charities also founded institutions for special populations, such as foundling hospitals for infants and unmarried mothers, and segregated homes for minority children.

The Civil War (and later, the Spanish-American War) caused thousands more children to become orphaned or indigent. Several states, counties and towns built homes especially for the children of sailors and soldiers. The Grand Army of the Republic created similar facilities.

Placement in an orphanage was often temporary. Parents or extended family might sign over custody of children until they could get back on their feet. In fact, the majority of children eventually returned to their homes. Children who were surrendered permanently became wards of the state.

If you think a child may have been placed in an orphanage, look for him first in the US census. As early as 1850, he should appear as an “inmate” of a home, listed alongside other residents. When you find children in an institution in the 1880 census, also look for their enumeration in the Defective, Dependent and Delinquent special census schedule, available for several states on Ancestry.com. Censuses of homeless and institutionalized children may include information about their parents, such as country or state of birth. If you can determine what facility housed a child, try to locate records. Search online for the facility’s name and location and look for:

- Record indexes on websites such as Ancestry.com or USGenWeb articles about the history of the institution, which may point to surviving records.

- Manuscript finding aids for original record collections at archives.

- The FamilySearch catalog also includes hundreds of microfilmed orphanage records. Find relevant ones by running a keyword search with the name of the facility or the word orphanage and the location.

Any surviving orphanage records are probably rich in detail. Records may include intake registers, surrenders of children (also called quit-claims) and even death and burial records for those who passed away in the home. Some individual files may be restricted, especially those that contain medical data. But you may at least be able to confirm a residence along with some family information.

Orphan Trains

Not everyone was a fan of the orphanage system. Some reformers thought children should be placed with families, preferably in rural areas, rather than spending their lives in regimented orphanages that didn’t adequately prepare them for adulthood. The most famous (or infamous) approach to this early version of foster care was the orphan train movement.

In the 1850s, an estimated 30,000 children in New York City were homeless. The Children’s Aid Society in New York struggled to care for them. Society leaders believed children faced brighter futures with rural families. The society began shipping children by train to mostly the Midwest and West. Willing families, responding to newspaper ads, showed up at the railway station, chose a child and filled out contracts to shelter and educate them. Older children would be paid for their work. In theory, the society tracked the welfare of each child, but in practice this proved impractical. Records created at the time and afterward showed that many children did well and some didn’t.

Nearly every US state, as well as Canada and Mexico, received orphan train children, with Indiana receiving the most. The New York Foundling Hospital, New York Juvenile Asylum and Orphan Asylum Society of the City of New York all placed children on orphan trains, as did institutions in Chicago, Boston and Minnesota. All told, about a quarter million American and Canadian children rode orphan trains in the last half of the 1800s and through 1929.

Today, a network of orphan train riders and their families researches their roots via the Orphan Train Heritage Society, housed at the National Orphan Train Complex in Concordia, Kan. The official archive of the Children’s Aid Society is at the New York Historical Society Museum & Library. The collection is rich in historical material and correspondence; however, much material from individual case files is restricted. Research services are available for those who can’t visit the library themselves. Find contact information for several institutions that participated in orphan trains here.

Start researching an orphan train relative with his or her appearance in federal and state censuses. Look for him both in institutions before placement and in homes afterward. Ancestry.com has a database of about 5,000 children who lived in Children’s Aid Society facilities during various state or federal censuses. Also research local newspapers for ads or articles about the arrival of the train. Several state-level orphan train groups and regional research facilities gather information about riders in their areas.

Adoption

Formal legal adoption is a modern practice that didn’t begin in the United States until Massachusetts passed a statute allowing for it in 1851. This law, quickly copied by other states, required the court to supervise adoptions and gave adopted children the right to inherit from the adoptive parents. By the end of the 19th century, laws generally required that courts consider the good moral character of the adoptive parents and their ability to support and educate the child. Informal adoptions, though, continued well into the 20th century.

Adoption records were public everywhere until 1917, when Minnesota passed the first law making them confidential. This protected the records from public scrutiny but left them open to adopting parents and adoptees themselves. By the mid-1940s, confidentiality gave way to secrecy: Many young girls were sent to homes for unwed mothers where they were pressured to surrender their babies for adoption. Records were sealed, and a new amended birth certificate issued listing the adoptive parents as the parents. Even the adoptee was unable to obtain a copy of the original record.

The change from open court records to confidential records to secret records makes adoption research a real challenge. Changes in access laws, however, have opened some states’ adoption records to both adoptees and members of birth families under certain circumstances. Essentially, all states allow adopted persons access to nonidentifying information once they reach adulthood. That may include the birth parents’ ages and general physical information, race, ethnicity, religion, medical history, education, occupations and existence of other children.

Some states disclose identifying details about adoptees and birth parents, often only with mutual consent. Roughly 20 states give some or all adoptees access to their original birth certificates. In still other states, adoptees and birth families must use confidential intermediaries to obtain information. If you’re looking for your birth family or that of a parent or grandparent, find summaries of states’ current access laws online.

Under the State Resources menu, choose State Statutes, scroll to Adoption topics and choose the specific subtopics. See also the American Adoption Congress website.

DNA testing is a relatively new tool available for finding biological relatives. Start with autosomal DNA tests, available from AncestryDNA, MyHeritage DNA, 23andMe and Family Tree DNA (look for the Family Finder test). Results can link adoptees to family members who’ve also tested, and verify biological relationships hinted at in paper trails. Tests work best when matching close relatives, and are least reliable for fifth cousins and beyond. Understand that the process is emotional for adoptees, their parents and birth families (who may not be aware of the adoption). Approach matches—and your own feelings—with a great deal of sensitivity.

No comments:

Post a Comment