The Genealogist’s Guide to Church Records

By Sunny Jane Morton

In 1926, roughly half the US population belonged to one of about 230,000 religious congregations across the country. Some churchgoers also attended Sunday schools, church socials, service auxiliaries and revivals; and sent their children to church-sponsored schools.

Such vigorous worship communities often produced vigorous records. Among them were membership lists, baptismal registers, marriage records and lists of deaths and burials. Maiden names, ages or dates of birth, relatives’ names and relationships, and prior or subsequent residences (including overseas birthplaces) may be sprinkled throughout these records.

Church records aren’t always easy to find or access, but online resources make this task easier. Online sources may help you identify an ancestor’s probable congregation. Web searches may lead you to sources of published or microfilmed versions and even digitized online records. This guide will get you started.

Types of church records

Before you set off in search of church records, consider when it’s worth searching for them. Records pre-dating the Civil War are more likely to be written freeform in blank books or on loose sheets, often with scant detail. Baptisms and marriages are the life events most commonly found, with the date of the event, witnesses or godparents, officiant, and (for children’s baptisms) names of parents. Deaths and/or burials were more likely recorded if the church had its own burial ground. Protestant faiths often created periodic roll calls of members or a master membership list with infrequent but valuable details like a spouse’s name or death date noted.

In the later 1800s, churches began using registers pre-printed with columns. Details varied by faith, congregation and even the scribe. Many Protestant faiths kept membership ledger books with separate lists of ministers and church officers, baptisms (with parents’ names for children), marriages (often with the couple’s residences) and deaths (sometimes with burial information). The dates of these events, officiants and sometimes witnesses were recorded.

Members of many Protestant denominations who migrated received letters of transfer admitting them to the new church. Membership ledgers may have notations such as “admitted by letter,” along with the previous city or church. When someone moved out, you may see “dismissed to” or “disposed of” with the destination and/or date. Rarely, letters of transfer survive in church administrative files.

Some Protestant faiths, such as Lutherans and Methodists, recorded more details than others. Baptist records are typically sparse. Record content also may vary based on beliefs or practices. For example, Quakers don’t baptize; therefore, they don’t have baptismal records. But records of Quaker marriages often include the names of everyone in attendance, the bride’s and groom’s residences and their parents’ names and residences (or an indication the parents were deceased).

Catholic parishes (the term for a local congregation) didn’t generally keep membership lists, but they did register sacraments—often in Latin and sometimes, for churches with large immigrant memberships, in a foreign language. Most often you’ll find records for:

- Baptism, often performed within a day or two of birth, with the date, godparents, child’s parents and the parents’ birthplace. Later sacraments in that child’s life also might be noted here, too, even if they occurred in another church.

- Confirmation, often received as a young teen, recorded as a simple list of those who received it and the date. Use this record to confirm a family’s residence at that time and participation in church life. More recent records may mention the place and date of baptism

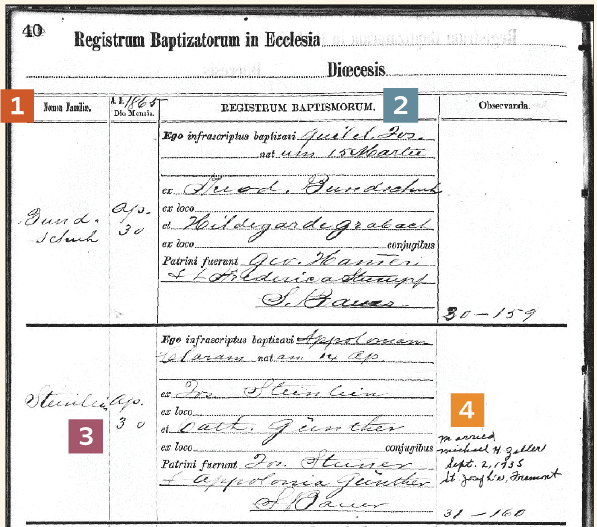

Example: Catholic Baptismal Register

|

- The columns shown are for last name, date of event, particulars of baptism and additional comments.

- These records are in Latin; even Latin forms of names may be used. “Guilel” is an abbreviation of Gulielmus, Latin for William.

- The translated baptismal record reads, “I, the undersigned, baptized Appoloniam Helaram, born 15 Ap[ril], of Jos[eph] Steinlein from place [blank] and Cath[erine] Gunther from place [blank], married. Godparents were Jos[eph] Steiner and Appolonia Gunther.”

- Comments include a note about Appolonia’s marriage, specifying her spouse’s name, the date and parish. Check that parish for records of the marriage and children’s baptisms.

Marriage and possible banns (formal announcements), if they were read prior to the marriage. Look for the couple’s name, parents’ names, witnesses and officiant’s name. More recent records may indicate baptismal place and date.

Extreme unction or last rites, performed for the dying. Look for notes about the dates of death and burial, burial place, and sometimes age at death.

Holy orders and taking of vows, for those who became priests or nuns. (Look for additional records in an archive for the religious order the person joined.)

Also look for denominational newspapers. Methodists published regional versions of the Christian Advocate (for example, the New York Christian Advocate or the Nashville Christian Advocate). Several Catholic dioceses published newspapers or newsletters, too. Many of these had limited runs in the late 1800s and included obituaries of members.

Identifying the right church

On the eve of the Revolutionary War, more than half of those in the English colonies were either Congregationalists (mostly in New England) or Anglicans (Church of England, dominant in the South). Others were Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed and in much smaller numbers, Quakers, Baptists, Catholics, Methodists and Jews. Spanish and French colonists were largely Catholic; a significant minority of French colonists were Huguenots.

That religious picture changed dramatically during the following century. Anglicans and Congregationalists lost government sponsorship and popularity. More experiential faiths took their place. By 1860, half the congregations in the US were Methodist and a quarter were Baptist. Another 10 percent were Catholic—a number that would grow as more Catholic immigrants arrived.

To determine what church might have records of your ancestors, make an informed guess based on these factors:

Family lore: Ask older relatives what churches family members attended throughout their lives. Check with distant cousins, too, especially those who still live near an ancestral hometown.

Records: An ancestor’s faith or specific church might be specified (or at least hinted at) in nonreligious records. Watch for a religion or church mentioned in an obituary or associated with a burial place (keeping in mind that a churchyard burial may have represented the religious wishes of other relatives, not the deceased). Research the affiliation of ministers who married or buried your ancestors. Look up the meaning of symbols on tombstones. Look for biographical details in funeral programs, county histories and other documents.

Transitions: The religious choices of one generation don’t always agree with the preceding one. Switching to a different faith might happen with marriage or migration away from relatives or to a place where the old faith didn’t have a foothold. As you trace immigrant ancestors, be aware that some ethnic groups assimilated faster than others. Watch for a transitional generation whose more “American” naming patterns or dress are distinct from those of the previous generation. This may be a key time to look for clues pointing to an “Old World” religion.

Ethnic group: Immigrants often brought their country’s dominant faiths. English were often Anglican (a denomination that became the Episcopal church in the United States); Scots-Irish, Presbyterian; and Scandinavians, Lutheran. Irish, Italians, Spanish, French and many Eastern Europeans often were Catholic. Germans had the most variety: Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, Jewish and many smaller sects.

Conversely, members of many religious groups—English Quakers or French Huguenots, for example—came to the United States because they didn’t agree with their national faith. Consult history books to learn the overall religious picture of your ancestor’s ethnic or national group, including dissenting or “nonconformist” sects that migrated during that time period.

Immigrants from the same place and who shared a religion often settled together in America. Those initial religious cultures evolved with the changing times and residents. A region of the South that was primarily Anglican during one generation may have become mostly Methodist or Baptist within a few generations. Research local history to learn about these patterns.

Proximity

The nearest reasonable option may have determined a family’s place of worship. Many Congregationalists who went west from New England joined Presbyterian churches, which had a similar culture. Migrating German Lutherans may have joined ranks with local Reformed or similar German sects. City directories and neighborhood maps showing property ownership or local landmarks can help you identify the churches nearest your ancestors.

Some Catholic immigrants didn’t attend the parish nearest their home. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, ethnic parishes served German, Irish, Italian, Slovak and other Catholics who wanted to worship in their own languages. Local histories or a Catholic diocesan archivist (see below) can tell you about local parishes that served your family’s ethnicity.

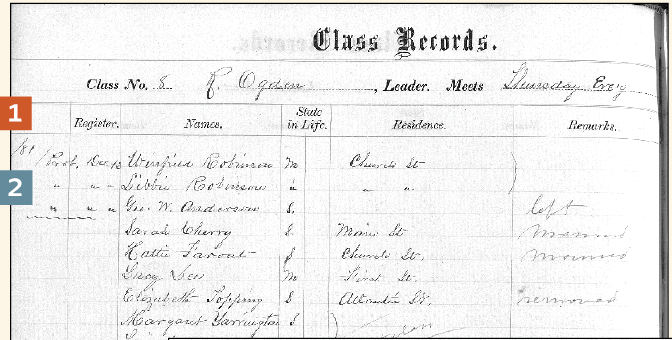

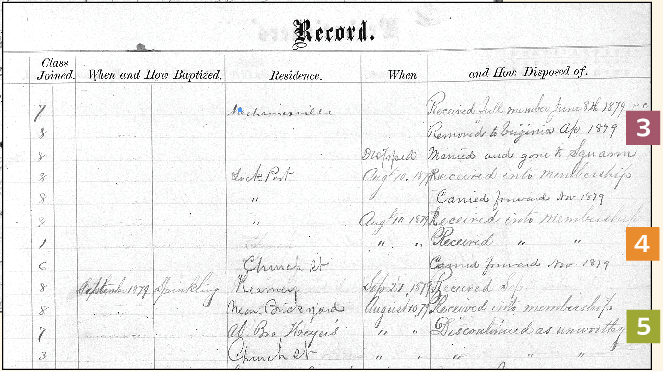

Example: Methodist Sunday School Register

|

- On continuing pages, the year may appear in an abbreviated format, such as 81 for 1881.

- Prob likely stands for “probationer,” a probationary member. Look for these names with further information on a probationer’s list in the register book.

- This migration information is a clue to look for individuals in their new places.

- If someone was “received into membership,” look for his or her entries in the member list in elsewhere in the register book.

- Notes such as ”discontinued as unworthy” or “discontinued—drunkenness” reveal more than just whether a person was present at Sunday school.

Accessing church records

Once you’ve identified a possible ancestral church, it’s time to start looking for its membership or sacramental records. These may exist in original manuscript, microfilmed, published and/or even digitized format.

Although Ancestry.com and FamilySearch have selected church records (including Quaker records on the former), for the most part, these records aren’t online. But you can start your search with your favorite web browser. Search for the name of the church if you know it, along with the denomination, city and state. As desired, add terms such as records, baptisms or marriages to narrow search results.

Browse search results for websites of churches. Also watch for any mention of records in online manuscript finding aids, genealogy website databases, on microfilm or in published format at a library (more about these below).

If the local church exists and has a website, your search should bring it up. If you can’t find one, search for the name of the denomination and the phrase “church locator.” Most denominations have online tools to help you find their churches in specific locales.

Look for history information on the website to confirm that this church existed during your ancestor’s life, was in the right place and, if applicable, matched your family’s ethnicity. Most congregational websites don’t mention whether they have old records, but it’s worth browsing the site to see.

You should at least find contact information for the church office. Send a brief inquiry about membership or sacramental records for the time period in question and the procedure for ordering them. Ask whether they would direct you to records if they exist elsewhere. Be polite and patient. Church offices aren’t obligated to fulfill genealogical requests. Mention your willingness to pay for a researcher’s time or to make a donation to the church.

Your ancestor’s congregation may have dissolved or merged with another one. In that case, conduct a web search for a denominational archive. Consult the toolkit on the previous page for a starter list. Some churches maintain a central archive or have archival collections at universities. Other churches have regional archives, such as Methodist conferences and Catholic dioceses. These may hold old records of congregations within their boundaries. Contact archivists about how to access historical records from the church and time period in question.

Tip: When requesting copies of records from churches and religious archives, be respectful and patient. Church offices aren’t obligated to help genealogical researchers.

If the denomination itself doesn’t seem to exist anymore, consult a denominational family tree like the ones at the Association of Religion Data Archives website. You’ll learn important details. For example, Congregational churches now exist under the banner of the United Church of Christ. This may help you to locate existing successor churches or contact an appropriate denominational archive.

The Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City has many church records on microfilm. On the FamilySearch website, click Search, then Catalog. Search by place: Start typing the town, city, county or state, then choose from the dropdown menu that appears. In your search results, click Church Records. You’ll see a list of the FHL’s church records holdings for that place; click each one for details on the type of record and time period covered.

Some church records end up in private archives, too. Watch web search results for online finding aids or record collection descriptions. Use Archive Grid, an online catalog listing millions of records, to search for archives near your ancestor’s home. Also conduct a targeted search for published and/or microfilmed congregational records. Start with WorldCat, an online catalog with over 2 billion items in libraries worldwide. Enter the same types of search terms as previously described.

Besides membership and sacramental registers, archives’ collections of church records may include church histories, denominational newspapers, administrative minutes, changes in membership status and occasionally members’ significant life events. Separate records may cover women’s or other service auxiliaries. Financial records, including itemized donation lists, also may mention your relatives.

If you find index-only versions of records, try to track down the originals. They’ll expose any errors in the indexed information and provide additional information that wasn’t in the index. Some Catholic sacramental records are considered confidential. Church records are released at the discretion of the record custodian, whether it’s a local priest or diocesan archivist. If you can’t get photocopies of a record, you might be able to at least receive a certificate with basic sacramental information transcribed onto it. Request that every piece of information on the record be provided, not just what the certificate has space for.

Chronicling America can help you identify denominational newspapers to research. Click on the site’s US Newspaper Directory, 1690-Present to search for denominational titles. The Language, Ethnicity Press and Labor Press pulldown menus have options such as Anabaptist, Jewish and Catholic Labor Unions. Also try keyword searches like Catholic diocese or Lutheran. Click on a search result to look for microfilmed holdings you might borrow through interlibrary loan, or print holdings at libraries that may provide obituary searches.

Clues in church records

Church histories may have lists of members, substantial donors, churchyard burials or clergy. See whether mention is made of original church records still extant at that time. Scan the text to learn more about the religious community to which your family belonged. Other local or county histories may include historical sketches of the church, too.

Church records can solve several types of family history mysteries. They can provide evidence of vital events when government records conflict, weren’t created, or are missing. For some times and places, church records may provide the most likely or even the only source to mention births, marriages and deaths.

Tip: Don’t use a baptismal date as a surrogate for a birth date without evidence that it was an infant baptism.

They can resolve mysteries such as parents’ names, a woman’s maiden or married surname, the “illegitimate” circumstances of a child’s birth, an immigrant’s overseas birthplace, or a family’s previous or subsequent residence. They even can help you reconstitute a family group with all siblings, including those who died young and would otherwise go unnoticed. They can tell you about women and minorities, who were underrepresented in other records of the day. Finally, church records may give you a better understanding of your ancestor’s religious life and community.

When you come across records that require translation, try Google Translate for a single word or phrase. The FamilySearch wiki includes several foreign-language lists of common genealogical words. In the wiki search box, enter the name of the language and word list. Published genealogical guides for various ethnic or language groups may also include important genealogical words or phrases.

Fast Facts

- Records begin: generally with establishment of an individual congregation

- Jurisdiction where kept: individual churches’ administrative offices; denominational archives; government, university and private libraries and archives

- Key details: dates and places of birth, baptism, marriage, death and burial; sometimes names of family members, migration places and dates

- Search terms: name of denomination, church and/or congregation; plus the place and records, baptisms or marriages

- How to find in the FamilySearch catalog: Under Search, select Catalog. Enter the place in the Places search box, then look under the Church Records category.

- Associated/substitute records: records of birth, marriage, death and burial

A version of this article appeared in the September 2016 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment