By Maureen A. Taylor

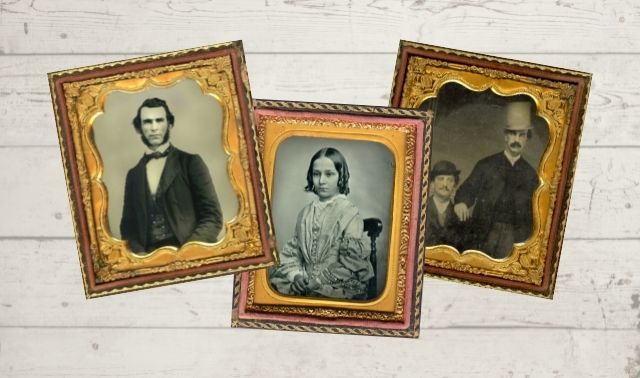

When an individual visited a photo studio in the late 1850s, he could choose the style of portrait—shiny reflective daguerreotype, glass ambrotype, metal tintype or a paper card photo. This is a key part of identifying a photo from the mid-19th century. If an image was taken before 1854, then it’s a daguerreotype, but if it was taken after that point, then it could be one of the others.

Daguerreotypes

Daguerreotypes, introduced in 1839, have a distinctive appearance. Because they’re reflective, you have to tilt them at a 45-degree angle in order to view the image. Otherwise, the silver-coated copper plate is often so shiny you just see yourself in the plate.

Ambrotypes

Ambrotypes, patented in 1854, are on glass. Backed with a dark substance (such as varnish or paper) they look positive, but when the backing starts to deteriorate, you can often see through the glass. This gives the image a ghostly appearance.

Tintypes

Tintypes, patented in 1856, are actually on iron, not tin. Unlike a daguerreotype, tintypes are not reflective. While you can find them in cases (like the previous two image types), most tintypes found in collections aren’t in any type of protective sleeve or case.

Paper cards

Card photographs (introduced in the United States about 1859) are on cardstock and instantly recognizable.

Case study: Daguerreotype, ambrotype or tintype?

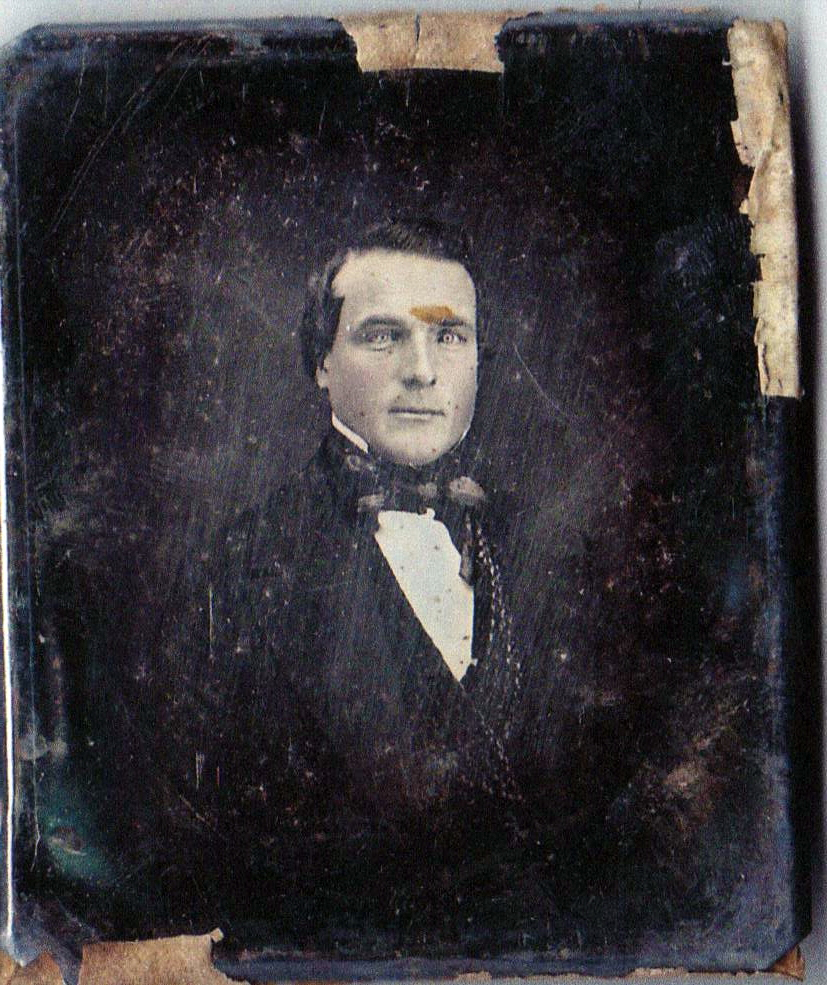

James Pennington posed for this photo about 1857, which means his portrait could be a daguerreotype, ambrotype or tintype.

Jay’s cousin sent him the pictures digitally. When she photographed the images, she propped them on a dark surface to decrease the reflection. Plus, the image has a type of deterioration known as a halo, usually found on daguerreotypes. I’m leaning toward it being a daguerreotype, but sometimes a digital image can be deceiving.After reading Jay’s family history website, it’s pretty clear when James posed for this image. He married his wife Esther Inwood in 1857. Both James and his bride are dressed for the occasion. (If you’d like to see a wonderful example of how to present your family history on the web, take a few minutes to look at Jay’s site on James Pennington. You’ll find everything from narrative to documents and DNA.)

No comments:

Post a Comment